Cultural Appropriation: Identity

- reconciliactionyeg

- Nov 14, 2022

- 4 min read

Tansi Nîtôtemtik,

This week, the Reconcicli-ACTION YEG writers are continuing our November theme of cultural misappropriation, and as promised, we are going to explore the topic of Indigenous identity. As a group, we decided that in order to best cover this sensitive topic, our Friday writer would introduce the topic so that we could close the week with an Indigenous perspective via our Monday writer.

In recent years, there has been no shortage of high-profile exposés on individuals whose claims of Indigenous ancestry are being questioned. The media has dubbed these individuals as “pretendians,” “Karenindians", “wannadians”- words for people who are, for the most part, participating in intentional deception for personal gain. There are, of course, others who are mistaken or embellish a very small part of their genetic makeup as their cultural identity. And there are also those who, through Canada’s colonial project, and through no fault of their own, had their identities threatened and damaged, leading to a strained connection to their cultures and their communities. Across Canada, conversations are taking place about what makes someone, anyone, a member of a particular group. Can a claim rest on the thinnest of genealogical needles? There is no easy answer. Identity, for any culture, is a touchy subject, and unfortunately, there is no clear formula for claiming indigeneity if you fall outside the Indian Act. So today, to start the conversation for the week, we are discussing the legal framework around Indian Status under the Indian Act.

Indian Status is the legal standing of an individual registered under the Indian Act.[1]

Indian Status dates back to 1876 when the Canadian Government developed criteria, which can be found in section 6 of the Indian Act, for who they would consider an “Indian.”[2] Nearly 150 years later, the Canadian government, through their Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) department still maintains an Indian Registry. Individuals on this registry are considered Status Indians and are issued status cards containing information about their identity, their band, and their registration number.

The criteria, or rules, around claiming Status are complex. Historically, there were sex-based inequalities that affected registration entitlements which resulted in the amendments to the Indian Act between 1985-2019, which include:

● Bill C-31 restored entitlement to women who had lost entitlement due to marriage to a non-entitled man, entitling their children to registration as well

● Bill C-3 granted entitlement to grandchildren of certain women who regained entitlement under Bill C‑31

● Bill S-3 took another step toward eliminating sex-based inequities not addressed by Bill C-31 or Bill C-3, entitling all descendants born before April 17, 1985, or from a marriage that occurred before that date, of women who had lost their entitlement due to marriage to a non-entitled man [3]

We could cover Indian Status for an entire school year, but for today’s blog, we will discuss status after the Bill C-31 amendments. Today, people are either status under either 6(1) or 6(2) based on the degree of descent from ancestors who are or are entitled to be registered.[4]

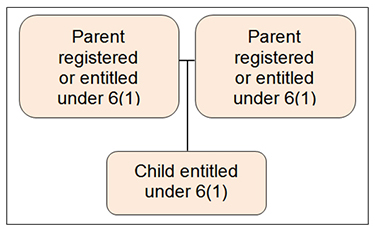

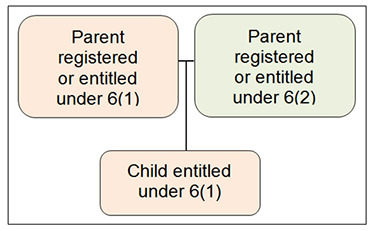

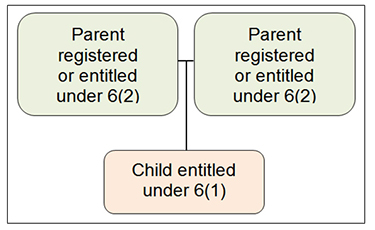

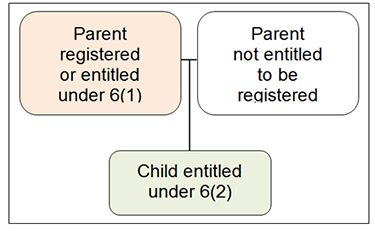

Individuals under 6(1) can be registered as Status if at least one of their parents is registered or entitled to be registered under section 6(1) of the Indian Act OR both parents are registered, or entitled to be registered under 6(1) or 6(2). If a person registered under 6(1) has a child with a person not entitled to be registered, their child would be registered under 6(2).

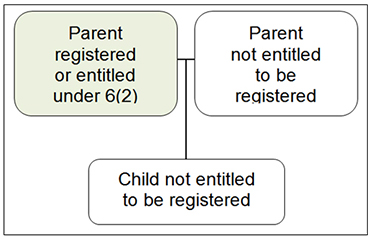

Photo Caption: The Five flow charts provided by https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs.html

The difference between 6(1) and 6(2) is important, as it affects your ability to pass along status. If you are registered under 6(2) and married a non-status person, your children would be ineligible for status. This is also known as the second-generation cut-off. “A person accorded status under subsection 6(1) does not face this penalty.”[5] However, it is interesting to note that if two individuals registered under 6(2) marry and have children, their child will become 6(1). [6]

While there are no differences in the access to services and benefits under 6(1) or 6(2), the second-generation cut-off is seemingly a new mechanism that “perpetuates the discriminatory measures of the Indian Act before Bill C-31, as certain [individuals] face penalties for “marrying out,” or marrying (and subsequently having children with) a non-status person.”[7] It has been said that this rule maintains the Government's “original objective of eventually removing Indian status entirely…; Bill C-31 simply deferred it a generation.”[8] The Indian Act, however, only applies to Status Indians and has historically not recognized Métis and Inuit peoples. As a result, members of these groups and non-Status Indians do not have rights conferred by Status despite being Indigenous to Canada and participating in Nation building. Join us on the blog throughout the rest of the week as we explore this topic and many other issues surrounding identity and cultural appropriation.

Until next time,

Team Reconcili-ACTION YEG

[1] Indian Act, R.S.C., 1985, c.1-5 [2] Ibid, s 6. [3] “Update on eliminating known sex-based inequities” (11 October 2022), online: Government of Canada <www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1462808207464/1572460627149>. [4] Ibid. [5] Karermen Crey and Erin Hanson, “Indian Status: What is Indian Status” (last visited 12 Nov 2022) online: UBC: Indigenous Foundations Art <www.indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_status/.> [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. [8] Ibid.

Comments